THE RCN ON D-DAY

Page 7: Conclusion

Originally

published in the "Crowsnest Magazine" Vol. 16 No. 5 May

1964

By Lt. Peter Ward, RCNR

|

|

|

|

|

As the days wore on, German attempts to challenge allied power in the Channel became less frequent and port after port fell to the Allies in Europe. The English Channel and the western approaches became truly Mare Nostrum.

BY

SEPTEMBER the Allied forces were almost unopposed by surface ships

in the Channel and approaches but the freedom of those waters had

been brought with the death of many fine men and ships.

Although

losses occurred during the invasion period, so well had the work

of preparation been done, so thoroughly had enemy ships been harassed,

gun emplacements pounded and mined areas swept, the Royal Canadian

Navy suffered no ship losses on D-Day itself, apart from small assault

craft, holed and battered by beach obstructions.

The

first major loss of the invasion was that of the Athabaskan, mentioned

above. The next loss within the invasion area (the frigate VaiZeyfield

was torpedoed and sunk off Newfoundland a few days after the Athabaskan’s

loss) was the Canadian motor torpedo boat 460, mined in the English

Channel on July 2, with the loss of 10 lives. Four men were injured

when MTB 463 was mined and sunk on July 8.

HMCS Matane, a frigate, was hit by a glider bomb in European waters on July 20 but made port.

On

August 6, the corvette Regina was sunk in the Bristol Channel with

heavy loss of life and 15 days later another corvette, the Alberni,

was mined or torpedoed, also with casualties.

Canadian minesweepers long opera ted in dangerous waters but it

was not until October 7, 1944, that they suffered their first casualty

when RMCS Mulgrave was damaged by a mine off Le Havre but did not

sink.

A disappointed

group of officers and men on D-Day was the RCN’s Beach Commando,

an outfit that had been training for months among the rugged hills

of Scotland, running assault courses, cooking, eating and sleeping

in the open, crashing ashore from assault craft on rugged beaches

and shrugging off the noise of thunder flashes and screeching bullets.

They

had trained hard for the invasion but they were not called on to

join the first wave. They did, however, go ashore on July 9 and

for many weeks helped to supervise beach traffic. They were the

trouble shooters and traffic police who guided landing craft to

safe stretches of beach and directed men and equipment to their

destinations. They looked after the return traffic, too — the

wounded and prisoners of war.

They

set up living quarters in abandoned enemy bunkers and gun emplacements,

quarters they sometimes had to reach by skirting areas still posted

with skull-and-crossbones signs that read “Achtung! Minen!”

where the German minefields were still uncleared.

It was a rough life but one for which their training in Scotland had prepared them well and one Ontario sailor waved any suggestion of hardship aside with: “It’s just like a glorified camping trip.”

D-DAY, Operation Overlord, was truly the end of the beginning. Canadians everywhere can remember with pride the 10,000 men in their little ships of the RCN who played such a vital part in making sure Overlord, the end of the beginning, turned into the beginning of the end.

|

|

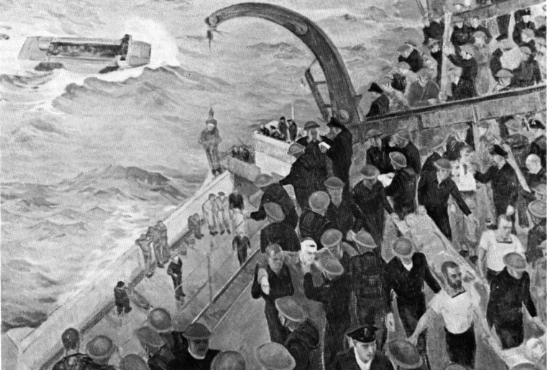

Cdr.

Harold Beament painted the scene onboard a Canadian landing

ship while the first casualties were being returned to the

ship. (HN-1628)

|